HIGH MIX: Unfriendly Robots, Forever Chemicals, Cookie Cutters

Reindustrialization news for September 15, 2025

Welcome to HIGH MIX, our weekly newsletter about the reindustrialization of the United States.

“Chemical manufacturing made New Jersey the ‘PFAS toilet for the country’” NJ SPOTLIGHT NEWS

Greetings from the land of diners, tolls, Taylor Ham, and, apparently, "forever chemicals." As a proud New Jerseyan, where the air still carries that faint industrial tang on humid summer days, this story hits a little close to home.

You might not be aware of our state's sordid history as the dumping ground for polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—those persistent pollutants lurking in everything from Teflon pans to firefighting foam. Shawn M. LaTourette, our Commissioner of Environmental Protection, nails it with a blunt quote:

"In effect, DuPont used the state of New Jersey as the PFAS toilet for the country."

I speak on behalf of (most) New Jerseyans when I say we don’t like being used as a toilet of any kind. I'm proud of our role in powering America's postwar boom (and just about every other boom), but this legacy of dumping has scarred wetlands and aquifers, which I’m also particularly fond of.

Let's rewind to the root of the problem. New Jersey's chemical industry boomed in the 20th century, turning us into a powerhouse, especially along the Delaware and Raritan rivers. DuPont's Chambers Works site in Deepwater, a sprawling 1,300-acre facility near the Delaware Memorial Bridge, was ground zero.

DuPont shipped PFAS waste from factories in West Virginia and North Carolina to this New Jersey facility for disposal, making our state the national "toilet" for these "forever chemicals." Lovely.

According to LaTourette, profit was the motive: "The stuff is harmful, and they knew it was harmful, and they kept making it anyway, and they kept putting it in products anyway, because the getting was just too good."

That's the sordid part—profits over people, the environment and everything else.

They also left 15% of us (those on private wells) vulnerable to untested contamination.

PFAS, dubbed forever chemicals because they don't break down in the environment, were first flagged in the early 2000s. By 2006, New Jersey led the charge with the nation's first statewide water assessment, revealing widespread contamination in groundwater, soils, biota, and even shellfish.

Fast-forward to today, and the fight back is a long road. Cleanup is difficult both technically and logistically—you have to interrupt PFAS at multiple points in the water and carbon cycles to get rid of them.

There’s been a landmark $2 billion settlement with DuPont and affiliates, announced last month—the largest environmental payout by a single state. It includes $875 million in cash and up to $1.2 billion for cleanup at four former sites. From my perspective, this settlement is a small win for accountability—force the polluters to pay, echoing the Superfund era when Jersey led in toxic site cleanups.

But it's not enough: contamination lingers in unexpected places, like remote forest soils, and health risks—cancer, immune issues—from these "forever chemicals" persist. That’s the whole reason for concern, they don’t break down. You have to remove them.

China’s heavily invested in chemical production, making over 60% of the world’s PFAS, thanks to lax environmental oversight that’s a nightmare for the planet. Some argue we should loosen environmental regulations across the board to compete, mirroring China’s cheap production edge, but that’s too far.

Deregulating to that extent risks turning the nation into a much bigger “PFAS toilet”. A non-stick cesspool, even.

New Jersey's chemical production sector still employs thousands, contributing 8% to our GDP, and it's evolving with greener tech. But the PFAS scandal reminds us that unchecked greed can poison the well—literally.

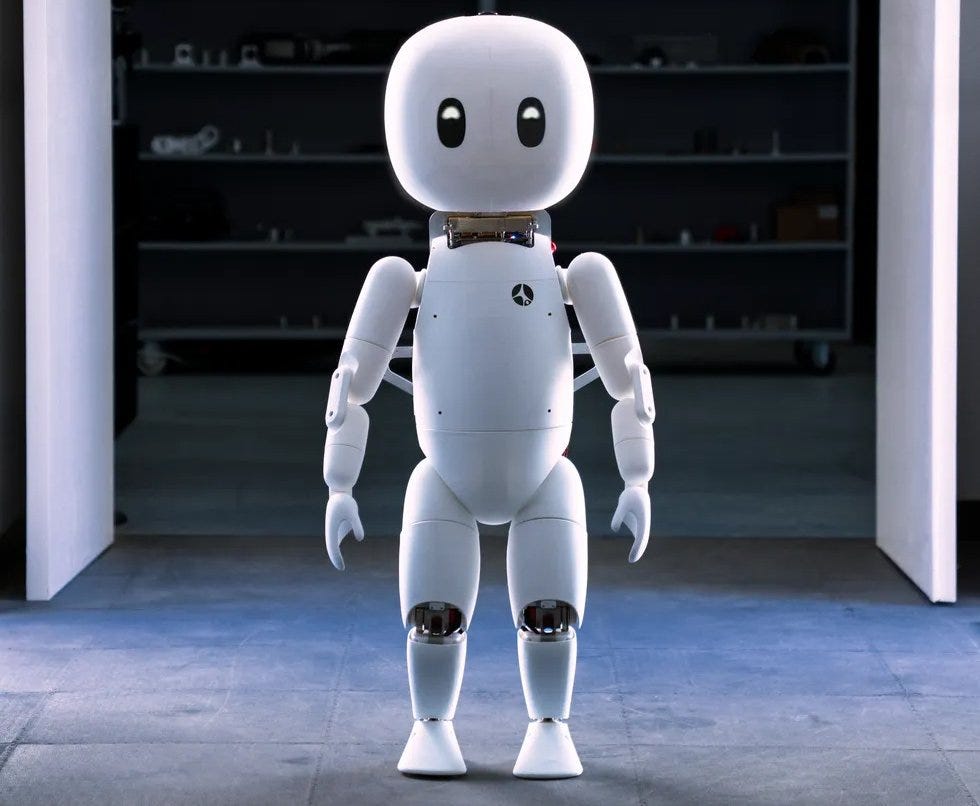

“Inventor who encouraged Elon Musk to make Optimus says most humanoid robots today are 'terrifying'“ THE REGISTER

Scott LaValley, CEO of Cartwheel Robotics, argues that today’s humanoid designs are missing the mark—not in capability, but in approachability. LaValley, a veteran of Boston Dynamics, warns that the current crop of robots, with their uniform, industrial aesthetics, come off as “terrifying” and “unfriendly,” alienating the very people they’re meant to work with.

"It's like rinse and repeat, every single humanoid robot looks the same," he said. "And they're all being designed by these automotive industrial designers. And they're just terrifying. They're so unfriendly. These are machines. These are tools. And they're unsafe."

LaValley’s vision for robot design is to start simple, and make them relatable. His company’s Yogi robot, a character “empowered with humanoid technology underneath,” prioritizes social cues over raw power.

Bipedal locomotion, actuation tech, and motion language models are advancing, but Cartwheel’s proprietary stack—eschewing the open-source ROS for Model Predictive Control—prioritizes stability over spectacle.

Challenges abound: safety, data privacy (especially with Chinese bots, where “there's a lot of concern and fear... that these robots can't be trusted”), and public perception, as LaValley recalls his son’s fear of Boston Dynamics’ Atlas versus his daughters’ delight at Baby Groot.

“Tim Cook details how Apple will put its $600 billion domestic manufacturing investment to work” CNBC

Tim Cook reiterates the company’s four-year pledge to pump $600 billion into reshoring, but he’s not really saying anything new here. It’s a polished recap of prior public disclosures, with the $2.5 billion Corning deal in focus.

Where’s the other $597.5 billion going?

Let’s start with what Cook does spotlight: the Corning expansion in Kentucky, a $2.5 billion infusion to scale Gorilla Glass production for iPhones and Apple Watches. This builds on the earlier announcement, where Corning’s new innovation center will drive R&D for advanced materials, ensuring durability for devices shipped worldwide.

It’s a solid move—Corning already supplies glass for every iPhone—but it’s hardly fresh news; the details were laid out in Apple’s August press release and a prior CNBC piece from August 6. The interview merely reinforces the partnership’s role in “stitching” the supply chain, a phrase Cook repeats to emphasize integration, but it stops short of specifics on timelines or output targets beyond the existing 9,000 U.S. partners and 450,000 supported jobs.

The Corning deal, while crucial for device durability, represents a tiny slice—perhaps 0.4% of the total pledge—leaving the lion’s share unaccounted for in this chat. Cook’s emphasis on “stitching” suggests a focus on supply chain, but without specifics on allocations for R&D, supplier expansions, or the Houston server facility for Apple Intelligence just to name a few, it feels like we’re missing a lot of information here.

Cook touches on semiconductor efforts, mentioning collaborations with Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC), Texas Instruments, and Applied Materials to “grow domestic semiconductor production.” He adds, “The president has said that he wants more in the United States. And we want more in the United States,” nodding to Trump’s 100% tariff on imported chips (exempt for U.S.-built ones). This aligns with the August announcement’s focus on end-to-end silicon—from wafers to packaging—but the interview offers no granular breakdown.

Where does the bulk of the funds go?

What we do know is that Apple’s strategy remains end-to-end: from raw materials (e.g., MP Materials’ rare earth magnets in Texas) to final assembly (Amkor’s Arizona packaging plant).

“Westminster Tool, Ward Leonard, Trumpf are 2025 inductees into American Manufacturing Hall of Fame” CT INSIDER

Launched in 2014, the American Manufacturing Hall of Fame (AMHoF) has now honored 40 companies, including heavyweights like ASML, Collins Aerospace, and Pratt & Whitney, with selections based on community contributions, workforce development, and economic impact.

This year's class—Westminster Tool (small manufacturer), Ward Leonard (medium), and Trumpf (large)—spotlights Connecticut. Let’s take a look at what makes them special.

Westminster Tool, founded in 1997 by Ray Coombs in Plainfield, Connecticut, stands as a beacon for small-scale excellence. With just 40 employees across facilities in Plainfield, Sterling, and Essex, the company specializes in molds for plastic medical devices and composite tooling for aerospace and defense, including F-35 fighter jet components. What sets them apart is their workforce ethos: 75% of employees had no prior manufacturing experience, yet average tenure is nine years, with ages averaging 37.

Ward Leonard, a Thomaston, Connecticut, stalwart since 1892, represents medium-sized resilience. Acquired nearly five years ago by Fairbanks Morse Defense in Beloit, Wisconsin, the company now employs 112 people (aiming for 130 by year-end) in a 140,000-square-foot facility. Specializing in motors, control systems, and electrical hardware for the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard—key customer Electric Boat (who make submarines)—it plays a vital role in defense manufacturing.

Trumpf, the large manufacturer category winner, has been a Farmington, Connecticut, fixture since 1974, with its North American headquarters there. The German-based firm employs about 500 in Farmington, producing machine tools and laser technology for sheet-metal and laser-cutting, used in aircraft, agricultural machinery, cars, and more.

“New center to shape the future of advanced manufacturing” VT NEWS

At its core, Virginia Tech Made integrates advanced materials, manufacturing technologies, computational design, data analytics, and digital infrastructure to solve pressing industry challenges.

They’ve got a suite of facilities, including the Kroehling Advanced Materials Foundry, the Nanoscale Characterization and Fabrication Laboratory, and the upcoming Mitchell Hall with its 6,000-square-foot high bay laboratory. These spaces support nearly every additive manufacturing method, from 3D printing to hybrid processes, enabling research in robotics, automation, cyber infrastructure, augmented and virtual reality, and next-generation materials.

Key projects include a $4.2 million cooperative agreement with the U.S. Army Research Laboratory for additive friction stir deposition—a solid-state method that joins metals without melting them—and nearly $3 million from the National Science Foundation for robotic additive manufacturing using digital twins, which simulate real-world performance to optimize designs.

In 2024 alone, affiliated researchers secured over $10.7 million in new funding and $34 million in ongoing awards for manufacturing-related efforts, underscoring the center's momentum. Strategic investments in higher education and research are the best bang for our buck.

The center's value to the country is multifaceted, particularly in workforce development. Virginia Tech Made will expand outreach to K-12 students to spark early interest in manufacturing, while offering continuing education for engineering professionals. This includes hands-on modules in undergraduate engineering courses, creating a "manufacturing spine" in the curriculum, and events this fall on economic and workforce development.

Julie Ross, vice president for research, notes, “We’re not just responding to where manufacturing is going, we’re helping to lead it.”

“Why this manufacturer isn’t crumbling under tariff pressure” SUPPLY CHAIN DIVE

In the quaint town of Rutland, Vermont, where the Green Mountains meet the realities of global trade, Ann Clark Cookie Cutters stands as a testament to strategic foresight in an era of escalating tariffs.

This family-run manufacturer has weathered the storm of U.S. trade policies with remarkable ease, thanks to a pivot to in-house production over two decades ago. Led by CEO Ben Clark, the company—known for its whimsical, handcrafted cookie cutters shaped like everything from gingerbread men to holiday themes—has transformed potential disruptions into a competitive edge.

With a lean manufacturing operation that keeps inventory low and flexibility high, Ann Clark exemplifies how small-scale U.S. producers can thrive amid the tariff turbulence.

The company shifted to producing its cookie cutters domestically more than 20 years ago, a move that predates the current wave of protectionist policies. This in-house approach means most inputs are sourced from within the U.S., insulating the business from the full brunt of import duties.

In practical terms, this translates to a streamlined supply chain where raw materials like steel and plastic are procured locally, avoiding the 25% tariffs on Chinese imports that have hammered other sectors. For a company that crafts over 100 designs annually, this agility is crucial—sudden spikes in demand, such as holiday orders for pumpkin or snowman cutters, can be handled without the delays or cost spikes that plague import-reliant firms.

What makes this case particularly insightful for the manufacturing landscape is its demonstration of resilience at a small scale. In an industry where tariffs have driven up costs for imported components by 20-30% across sectors like appliances and automotive parts (per recent Commerce Department data), Ann Clark's domestic focus has shielded it from the worst.